Cycle Detection

Finding cycles over an iterable function is a problem that commonly pops in many forms in many different applications. Common places where you may encoounter this include finding infinite loops in code and determining when you have a deadlock between multiple transaction calls in a database. (think two queries which rely on each other - there isn't enough information to run either query).

Often, a more complex problem can simply be reduced to this problem, making it important to not only memorize but understand the solutions to such a problem.

To illustrate how various solutions work, we're going to tackle the following problem: Given that you have an array where there are integers where each integer is from to inclusive, find the repeated number.

At first glance, this seems to have nothing to do with cycle detection. The obvious solution to this problem seems like creating a hashset and then inserting until you try to insert something that's already in the set, like so:

int solve(vector<int> numbers){

unordered_set<int> no_duplicates_numbers;

for (int i : numbers){

//if the number already exists in the set, then it's the duplicate

if (no_duplicates_numbers.find(i) != no_duplicates_numbers.end()){

return i;

}

no_duplicates_numbers.insert(i);

}

//invalid input (no duplicates)

return -1;

}

However, note that the time complexity of this is , as we perform the insert and find operations on all elements. In addition, the space complexity of this is , as we have to store every unique number in a hashset. At this point, we've already concocted a pretty good solution to this problem. In 99% of cases, this solution would be enough, as it's short and also easy to read and thus maintain.

However, can we do better? Of course.

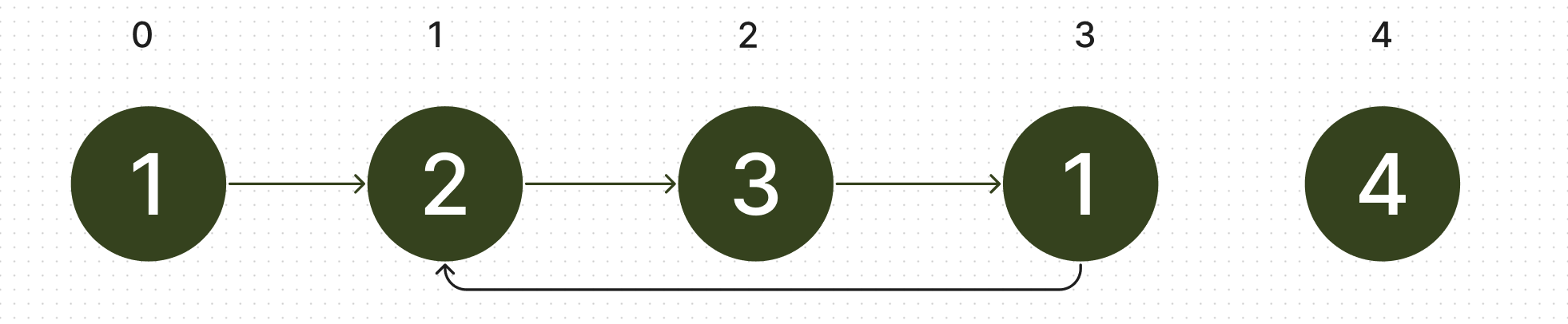

Though it may seem like cycle detection is irrelevant to this problem, it becomes clear that it certainly is relevant if we switch our representation of the problem. Let's take the case where the array is . We represent this list as a series of linked list nodes, one for each index. The value of the array at each index corresponds to the node that is at that index value. For example, if we're trying to find what the node at index 2 is doing, we notice that it's value is 3, indicating that it points to the node at index 3. Doing that for every node, we get the following graph.

Note that there's two pointers to the node at index 1. Looking at this list, it's clear that there's a cycle which contains the nodes at indexes 1, 2, and 3. We notice that the start of our cycle is at index 1, because there are two nodes pointing towards the node at index 1. Indeed, the duplicate number in our list occurs if and only if there are nodes with duplicate values pointing to the same node.

Note that there's two pointers to the node at index 1. Looking at this list, it's clear that there's a cycle which contains the nodes at indexes 1, 2, and 3. We notice that the start of our cycle is at index 1, because there are two nodes pointing towards the node at index 1. Indeed, the duplicate number in our list occurs if and only if there are nodes with duplicate values pointing to the same node.

Now, we've simplified our problem. Since the duplilcate number of our list is always the list that has multiple nodes pointing towards it, we want to know how to find that index that has multiple nodes pointing towards it. Now, we can consider our cycle. The start of the cycle always is the one that has at least two nodes pointing towards it, so we can simplify this problem further to finding the start of the cycle. This is exactly what cycle detection algorithms can do quickly. One common algorithms for cycle detection is Floyd's Tortoise and Hare.

Floyd's algorithm is simple, but somewhat unintuitive. We start with two pointers at the start of the list (index 0), one called slow and one called fast. We then start iterating: on each iteration, we move slow forward once to the node it's pointing to, while we move fast twice in the same way. When slow and fast are equal, we stop. We then leave the slow pointer where it is, and create a new pointer at the start. We'll call this pointer find_start. We move find_start and slow forward at the same pace until they are equal. The node they are at is the node we are looking for - the start of the cycle.

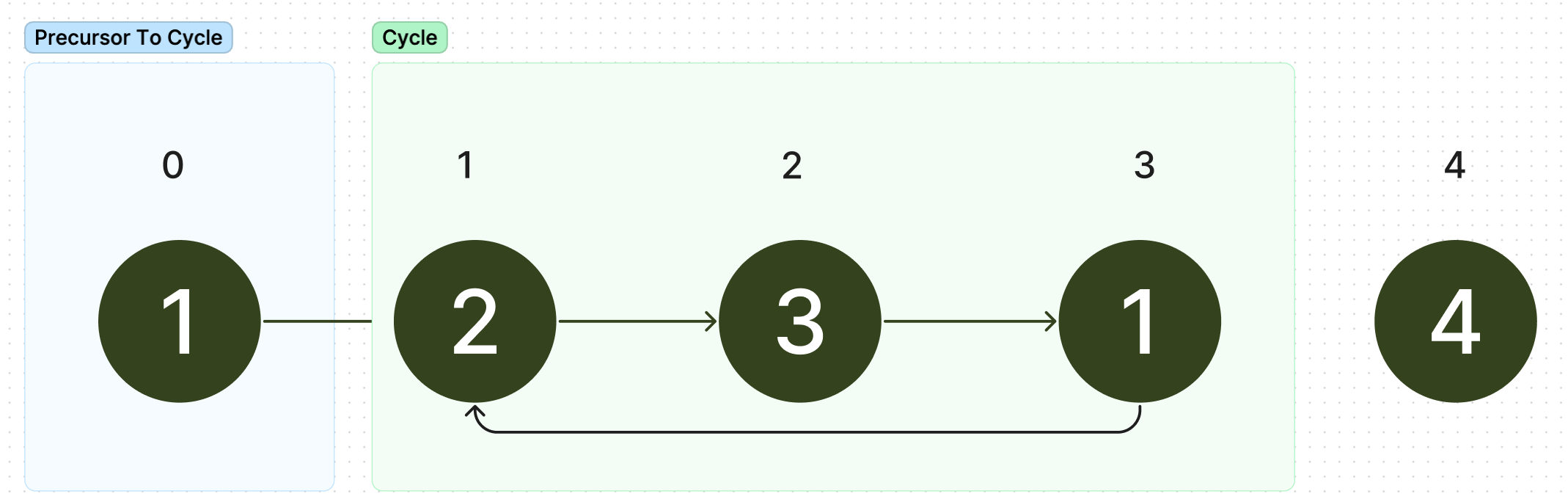

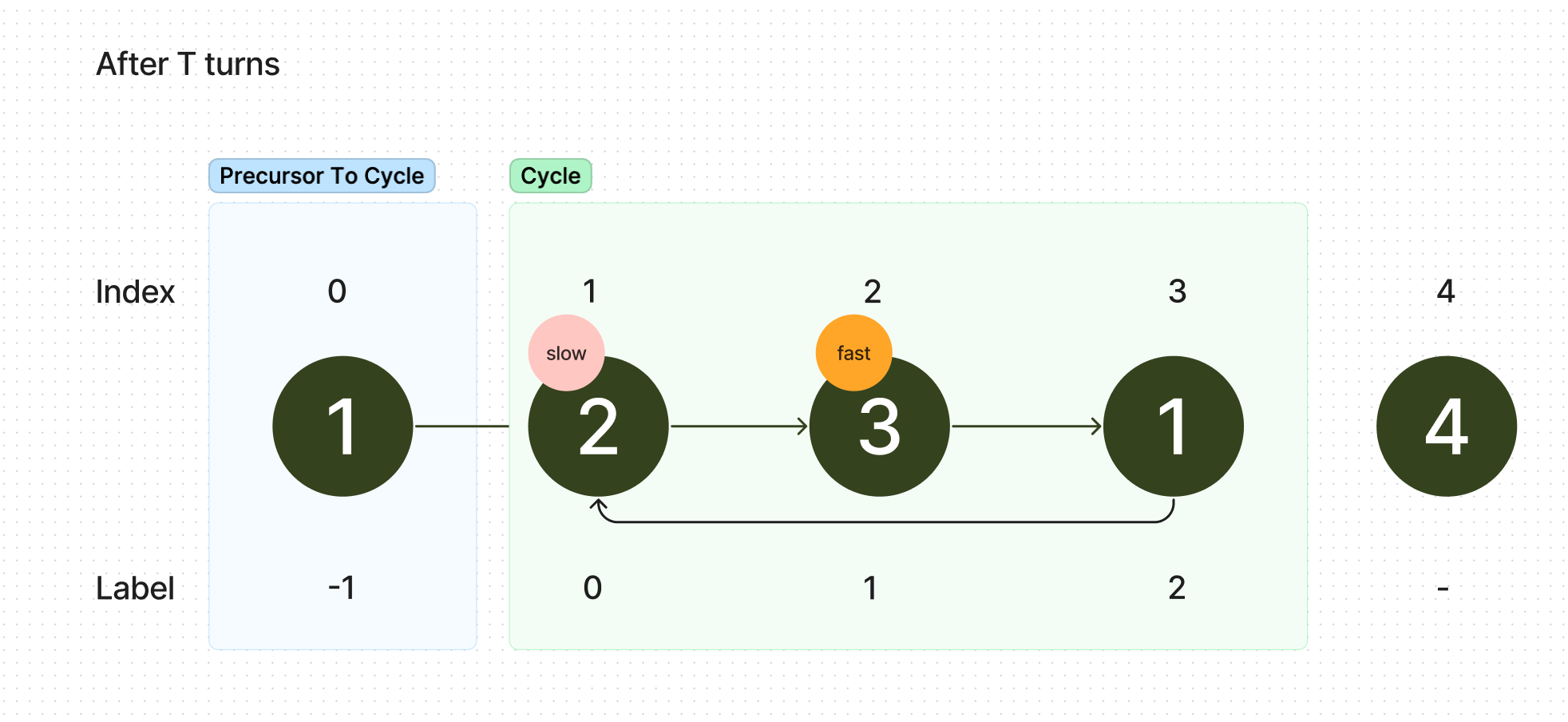

If you have some sort of a background in mathematics, perhaps the following will make this more intuitive, as we can prove that this algorithm is always true. We do this by finding two main parts of our graph: the precursor to the cycle and the cycle itself. In our example, it would be as follows:

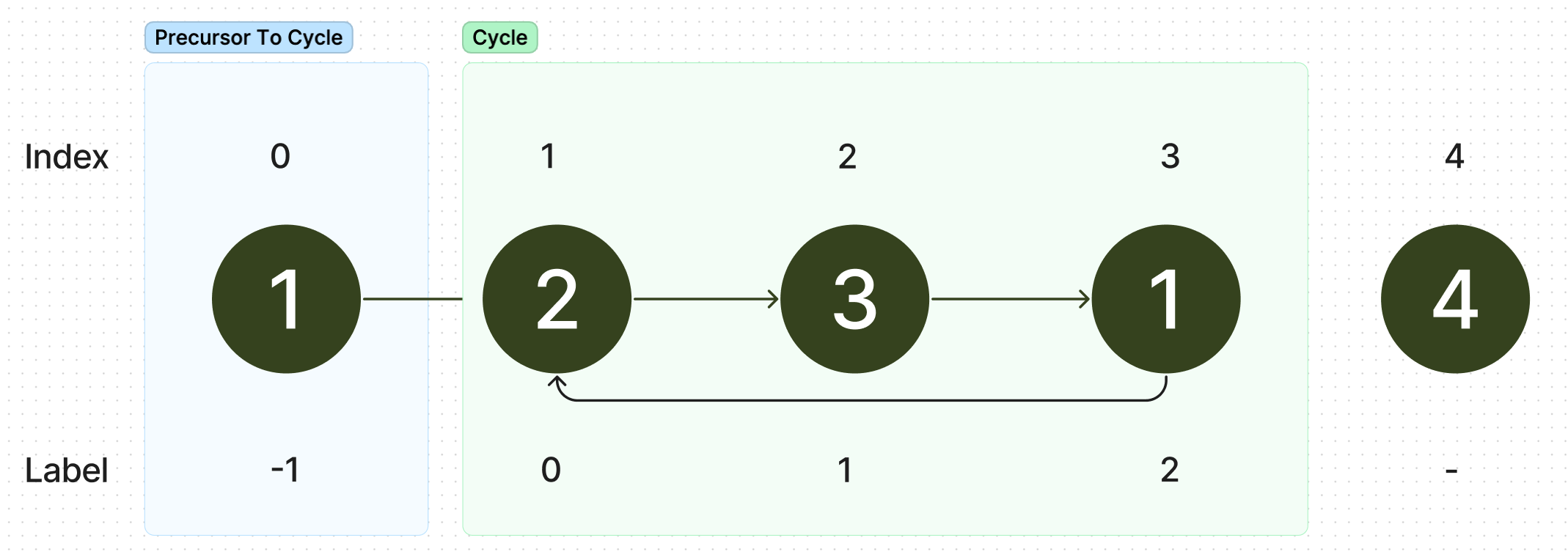

We need to note two things: the length of the precursor to cycle (variable ) , and the length of the cycle itself 0variable . We then give each node a label: the node at the start of the cycle (node at index 1 with value 2) in this example, is 0.

From this node, we travel backwards through the precursor to the cycle, giving the first node , the second etc until we reach the the start of the linked list. This node should have value . Labelling the cycle is similar - starting from the start of the cycle, we simply number the cycle going this time in forward order. Applying this to our example, we get the following.

The first thing we may do is use the division algorithm to write where for some .

We take a pause after taking "turns" where we move slow forward by 1 and fast forward by 2 to analyze where exactly slow and fast are. As we start both fast and slow at the node with label , and because fast moves twice as fast as slow, slow will have moved steps forward to 0, while fast will have moved steps forward. Since a cycle is infinite, we know that fast is somewhere in this cycle, at a node we'll name .

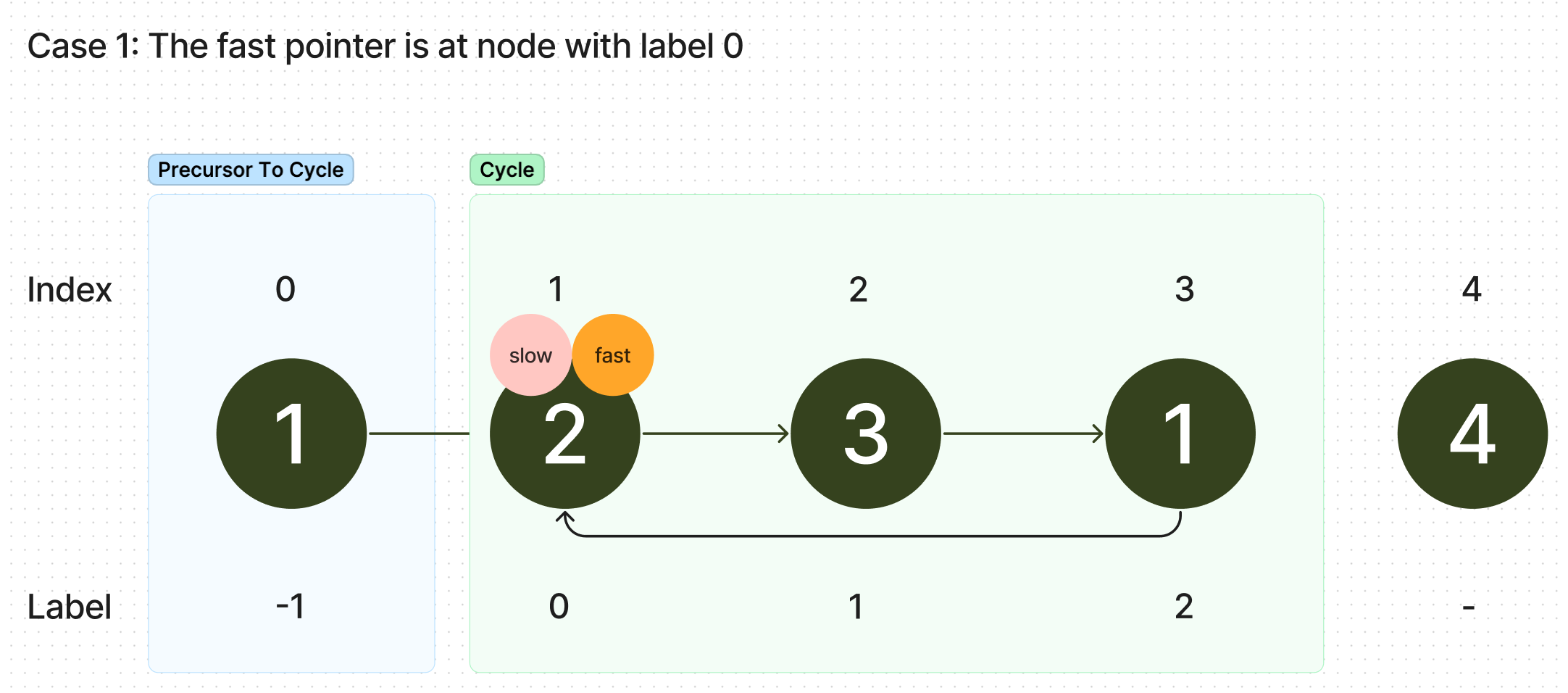

We now consider two cases: Case 1: the label of We're done in this case! Both the tortoise and the hare are at the same node, and that node is the start of the cycle. (the node 0 is always the start of the cycle).

Case 2: the label of

We notice that even though fast travelled a distance of , of those steps were spent going through the precursor to the cycle. Thus, fast travelled only a distance of through the cycle. We note that the distance can be written as where is some non-negative integer. This makes intuitive sense, as if the cycle was larger than , it would just be that . However, if the cycle was smaller than the distance fast wanted to travel, , the fast pointer would have done laps around the cycle with each lap being of distance , finally settling at node with label . We can write this with the modulo expression . If you've never seen modulo before, a good introduction is available here.

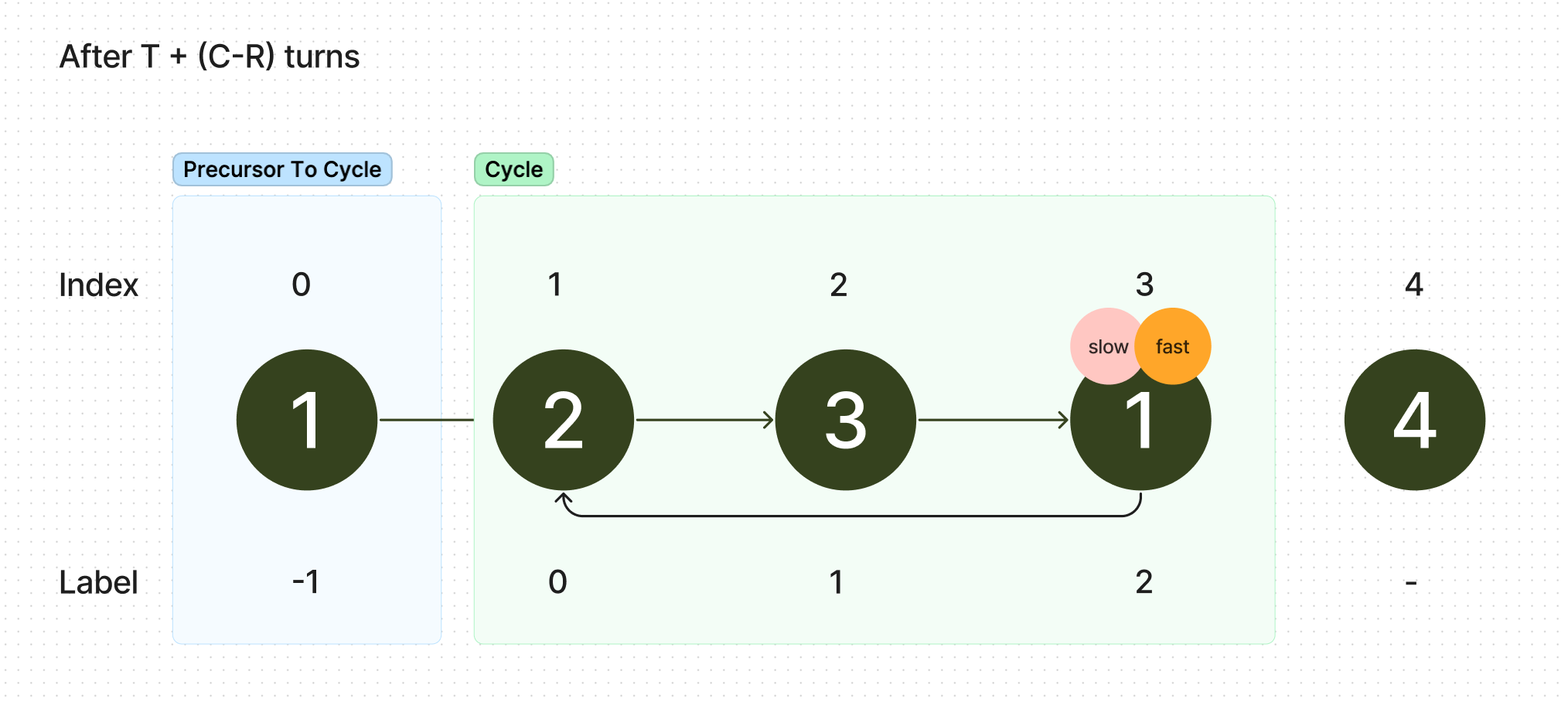

According to algorithm though, since fast and slow haven't met for the first time yet, we should keep on proceeding. After exactly more moves, slow will be at node . Because of the restrition on the division algorithm, , we note that this is always a node with this label within the cycle. In this same time, fast will have moved forward from a position of to a position of . However, notice how each multiple of is just a full lap around the cycle, so and are actually the same position in the cycle. Slow and fast have met at this point.

In our example, , so we need to wait for 2 more turns.

Slow and fast have now met somewhere in the cycle, at node with label .

The last step of our algorithm is to find the start of the cycle. We know that the start of the cycle is at 0, but it also is landed upon when a move is moved for a distance of some multiple of , as that just represents going though the entire cycle and landing back at the start of the cycle. In our code, we simply assume that after moving a node a distance of for a total of times, we end up back at the node with label 0, the start of the cycle. We're now going to prove that's true.

We recognize that our slow node has been moved forward times, and using our divison algorithm to substitute for , we get . Simplifying, we get , a multiple of . Thus, we always end up at the node with label 0, as no matter how many laps we take though the cycle, because we travel a distance that's a multiple of , we end up back there.

We've now proved our algorithm, so we can finally write the code implementing our algorithm.

int solve (vector<int> numbers){

int fast = 0;

int slow = 0;

//this loop executes the first T + (C-r) steps forward until fast and slow meet

do {

fast = numbers[numbers[fast]];

slow = numbers[slow]

} while (fast != slow);

/*

at this point, fast and slow have met, so we just need to move

T more times to get to the start of the cycle

find_start and slow_pointer will both be at the start of the cycle after moving forward T times

find_start will be at the start by definition, as the distance from the start to the beginning of

the cycle is defined as T

*/

int find_start = 0;

while (find_start != slow){

find_start = numbers[find_start];

slow = numbers[slow];

}

return find_start;

}

References:

Proof of Floyd's Algorithm: stackexchange link